Dhobighat's Unwashed Truth- Article

- Atmika Bhaskar

- Feb 11

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 9

(this project is part of MOJO which are done in three different forms of media)

Life, Labour and struggles in Mahalaxmi's Dhobhighat

By Atmika Bhaskar

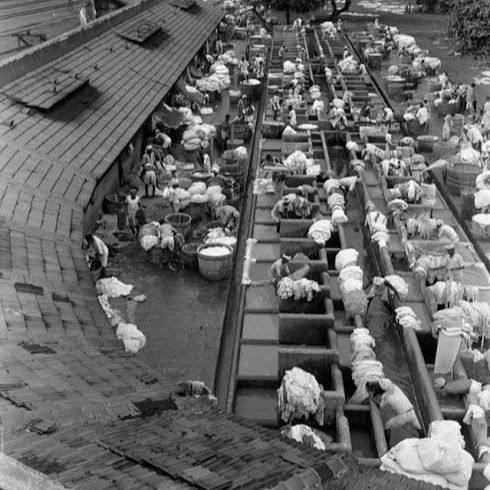

The steady thud of clothes hitting stone fills the air at Dhobighat, Mumbai’s vast open-air laundry. Tucked in the heart of Mahalaxmi, this is where generations of washermen and women have spent their days scrubbing, rinsing, and drying clothes. The scent of detergent clings to the air, mixing with the dampness of freshly washed fabric. Rows of stone wash pens stand in neat lines, their surfaces worn smooth by years of relentless work.

Dhobighat in the 1900s

Established in 1880 by the British, Mahalaxmi’s Dhobighat is divided into two sections: 631 large stones and 100 smaller ones, where countless dhobis have built their livelihoods. The washing pens, aligned in neat rows, are separated from the drying areas-open spaces where uniforms, denims, clothes, bedsheets, and hotel linens are hung on crisscrossing ropes. Some dry their laundry on top of their homes, while others use designated patches of ground scattered across the settlement. Hence, there are two sections- the washing grounds and the drying grounds.

Recognized as a 2B heritage conservation site by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), the area is at the center of a longstanding debate-should it be preserved as a cultural landmark, or should it make way for redevelopment? The people who live and work here are caught in the middle, struggling with deteriorating conditions, uncertainty about their future, and the looming presence of luxury developments.

A Community Rooted in Tradition

Life in Dhobighat follows a strict rhythm, dictated by the demands of washing and the movement of the sun. Over 200 families live here, though none own the land they work on. Instead, dhobis rent a small square with a flogging stone for about 500 rupees a month. Most workers are migrants from Uttar pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Andhra Pradesh, starting their day as early as 4 AM, long before the sun rises. By dawn, the washing pens are already filled with the sounds of scrubbing and rinsing. Breakfast, a communal affair around 9 AM, sees workers coming together-one kneads the dough, another chops vegetables, and soon a hearty meal is shared. As the sun reaches high noon, drying clothes becomes the priority, allowing for a brief midday rest. Work resumes by afternoon, with clothes removed from the lines, folded, and ironed. The cycle repeats daily, an early-to-rise, early-to-bed life dictated by the endless demand for clean clothes.

For many residents, Dhobighat is more than just a workplace-it is home. Veanila, a ninth standard student, has spent her entire life here. Her family migrated from the Hyderabad district of Andhra Pradesh 5-6 years ago and runs a washing business. “I like living here because everyone I know is close by,” she says. “It’s like one big family.” While she acknowledges occasional water shortages, she sees no major problem with life in Dhobighat.

However, for others, the reality is harsher. Saira M., originally from Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, has lived in Dhobighat for two years with her husband and two children. Their home is a cramped room with a tin sheet ceiling, offering little privacy. “I can’t breathe sometimes,” she admits. “It’s crowded, and sanitation is a big problem. I’d leave if I had the chance.

Among the dhobis, many hail from districts like Jaunpur and Azamgarh in Uttar Pradesh, and Darbhanga in Bihar. Riyaz Khan, a dhobi from Azamgarh, has been working here for 10 years, returning to his village only during festivals. “I send money home every month, but I can’t afford to bring my family here,” he says. The living conditions, with open drains and limited water access, make it impossible.

Women, who form a significant part of the labor force, often juggle washing with household duties. L. Kanaujia, 47, from Darbhanga, Bihar, starts her day at 5 AM, washing clothes before preparing breakfast for her children. “It’s exhausting,” she says, scrubbing a hotel bed sheet against the stone. “But what else can we do? This work is our identity. This is our parampara.”

For those born in Dhobighat, education is often secondary to work. Rubina Sheikh, 18, finished school last year but now spends her days assisting her mother in drying, ironing and folding clothes. “I wanted to study further, but we need extra hands,” she says. “Maybe after a few years, I'll get to do other things.” Many young women in Dhobighat face the same fate, bound by the demands of their family businesses.

While many dhobis continue to rely on traditional hand-washing methods, some families who have prospered in the business have invested in automation. Large washing machines, spin dryers, and steam irons have replaced the grueling manual labor for a few, allowing them to take on bigger contracts with hotels and hospitals. These families, often second or third-generation dhobis, have modernized their operations while still working within Dhobighat. “Machines have made our work easier, but not everyone can afford them,” said Rakesh, a dhobi and social activist. “Some have moved ahead, but most of us are still breaking our backs the old way.”

The living and working conditions in Dhobighat are harsh. Families squeeze into tiny, tin-roofed rooms with barely enough space to sleep. The constant exposure to chemicals, dyes and detergents leads to health problems, with cases of respiratory diseases and even cancer among workers. “We deal with chemicals every day, our hands burn, our lungs suffer, but we have no choice,” said Santosh Kanojia, chairman of the Dhobi Kalyan & Audhyogik Vikas Co-op Society. Sanitation remains a major issue, with open drains running between the narrow lanes and water shortages disrupting work. Despite these conditions, many choose to stay. Their businesses thrive here, and more importantly, they find strength in their close-knit community. Cooking, eating, and working together has built a deep-rooted sense of unity. “This is our parampara,” said Kanojia. “Our forefathers secured this place for us, and we protect it now.”

A Heritage Site in Decay

Despite its heritage status, Dhobighat’s infrastructure is crumbling. According to Krunal Bos, a sub engineer in the maintenance department of BMC’s G South Ward, the department is responsible for water supply, drainage cleaning, and security. Assistant Engineer Yadav adds that repairs are carried out monthly, and a complaint system exists for urgent fixes. However, no environmental impact assessments have been conducted, and there is little engagement with residents about their needs.

“The heritage committee (MHCC) limits what we can do,” Yadav explains. “Since Dhobighat is a 2B conservation site, repairs and modifications have many restrictions.” The deputy architect of MHCC, however, dismisses this claim, stating that G Ward has not put forward any strong proposals to truly preserve Dhobighat. “The inefficiency and ignorance of the engineers have resulted in this messy situation,” they state.

Santosh Kanojia believes conservation should not come at the cost of progress. “We have been protecting this tradition for years. Our forefathers secured this place for us,” he says. “But we need modernization-better water treatment plants, gas lines, and recycling facilities. We are suffering, and the government needs to act immediately,” Kanojia emphasizes.

The Redevelopment Dilemma

While conservationists argue for preserving Dhobighat, redevelopment efforts are already underway. The Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) was established in 1995 to provide formal housing for slum dwellers in Mumbai. Under the scheme, developers are incentivized to build high rise buildings for displaced families, while also securing land for commercial projects. In Dhobighat, real estate companies like Omkar and Piramal have acquired land, relocating 300400 families into 1 BHK apartments in SRA buildings.

However, not everyone is satisfied. Dhankar, who lived near the washing stones for years, was evicted for a bridge project and offered housing in Mankhurd. He refused, feeling it was too far from his work. Now, he commutes daily from Kanjurmarg, hoping for better compensation. “I have tried everything, but no one listens,” he says.

Jameela Ansari, 53, a widow from Jaunpur, was relocated to an SRA building in Worli. She describes the transition as difficult. “We were promised better living conditions, but the water supply is inconsistent, and the maintenance fees are high,” she says. Many SRA residents find themselves struggling with these hidden costs, making the move from informal settlements to high rise buildings less appealing.

A Future Uncertain

Despite their hardships, many residents remain protective of Dhobighat. They see it as a symbol of their profession and identity. “The government needs to recognize our service,” Kanojia says. “We wash your clothes. Protect us, give us better facilities.”

The MMRDA (Mumbai Metropolitan Region Heritage Conservation Society) has never funded conservation projects in Dhobighat. One employee notes that the site’s heritage lies not just in the washing stones but in the labor that takes place there. However, with real estate developers encroaching, that legacy is at risk. “Several builders are interested in buying property, but legal issues make it difficult,” they explain.

Conserving Dhobighat requires more than just its designation as a heritage site-it demands proper funding and planning. Without financial support, the open-air washing spaces, stone flogging areas, and communal drying grounds continue to deteriorate. Tushar Prabhoo,Vice President of the Indian Heritage Society, Mumbai Emiritus, who has closely followed the decline of traditional Dhobi Ghats, stressed the urgency of sustained investment. “Conservation isn’t just about declaring something a heritage site; it requires planning and funding,” he said. The Heritage Committee under the BMC (MHCC) should take an active role in ensuring maintenance, securing subsidies for operational costs, and advocating for essential amenities like a steady water supply and designated drying areas. Without these measures, Dhobi Ghats risk vanishing entirely, taking centuries-old skills and livelihoods with them. Beyond financial aid, proper sanitation and safer working conditions remain pressing concerns. Despite repeated demands for water treatment plants and better drainage, there has been little progress.

Meanwhile, Dhobighat is shrinking as builders acquire land under the guise of redevelopment. Real estate giants like Omkar and Piramal have already bought significant portions, leading to high-rise constructions that loom over the historic site. The value of these properties runs into thousands of crores, yet those displaced in the process receive little compensation. Activist and Dhobi Rakesh pointed out, “A building behind the Dhobighat, owned by Piramal, was sold for ₹2,650 crore, while the people who gave up their land didn’t even get ₹100 crore.” As luxury apartments encroach upon the space, the future of Dhobighat hangs in uncertainty, caught between heritage conservation, poor living conditions, and the interests of powerful developers.

For now, Dhobighat exists in a fragile balance between tradition and transformation. Some see it as a relic of the past, ready for redevelopment. Others see it as an irreplaceable piece of Mumbai’s history, in desperate need of preservation. But for the people who live and work here, the debate is not just about heritage or progress-it is about survival.

Continue on this journey as our writer Atmika Bhaskar delves deeper.

See the photo essay here

Listen to the audio podcast here

Comments